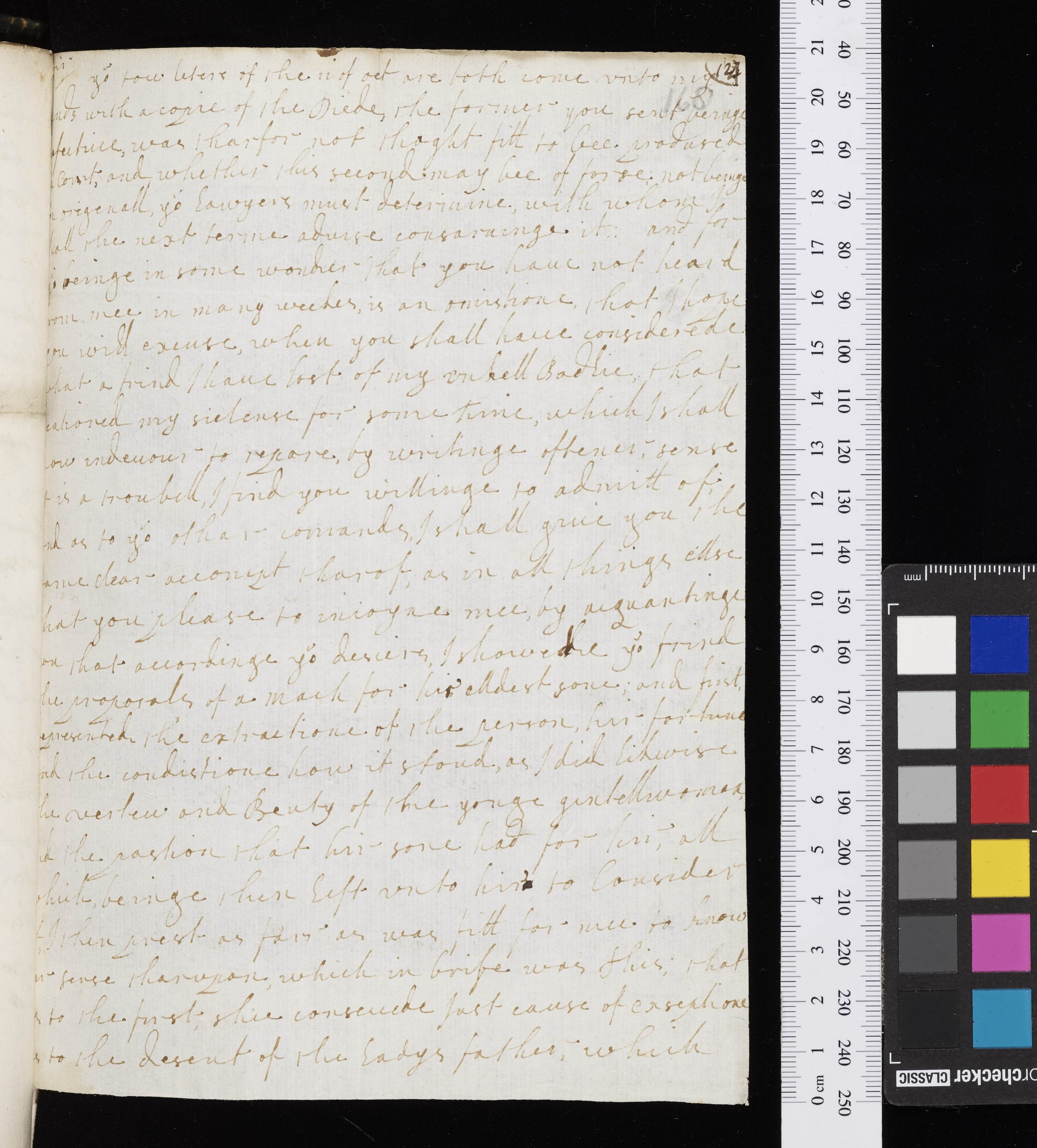

26 November 1658

The marchioness of Ormonde – writing in the guise of ‘JH’, probably from Dunmore House – to her husband, the marquis of Ormonde, whom she disguises as ‘Mr James Johnson’

Sir

your tow leters of the 11 of oct are both come unto my hands with a copie of the Diede, the former you sent beinge defective, was tharfor not thoght fitt to bee prodused in Court, and whether this second may bee of forse; not beinge an origenall, your lawyers must determine, with whom I shall the next terme advise consarninge it; and for also beinge in some wonder that you have not heard from mee in many weekes, is an omistione, that I hope you will excuse, when you shall have considerede what a frind I have lost of my unkell Badlie, that ocationed my sielense for some Time, which I shall now indevour to repare, by writinge oftener, sense it is a troubell, I find you willinge to admitt of; and as to your othar comands, I shall give you the [s]ame clear accompt tharof, as in all things ellse [t]hat you please to injoyne mee, by acquantinge you that accordinge your desiers, I showede your frind the proposals of a mach for hir elldest sone; and first, [r]epresented the extractione of the person, hir fortune [a]nd the condistione how it stoud, as I did Likwise [t]he vertew and Beuty of the yonge gentellwoman [a]nd the pastion that hir sone had for hir, all which, beinge then Left unto hir to Consider [of], I then prest° as farr as was fitt for mee to know hir sense tharupon, which in brife was this; that [a]s to the first, shee consevde Just cause of exseptione as to the desent of the Ladys father, which however not perhapes the less estimede in a Nother contrye, would make it of reproch heare; and secondl[ie] as to the fortune, which hee shee hears at the most is bu[t] tene Thowsand pound of which nethar the husban[d] nor his parents canbee the beter more then wha[t] the intrest of soe much cane bringe, shee conseves very inconsiderable, to the freeinge of an estate Morg morgedged for noe Les befor and sense the warr th[en] twentye Thowsand Pound, besids depts contracted for some years mantenanse, and the expense of recovring[e] it by Sute, and the yearlie rent with which it stand[s] Charged, besides tow daughters, yet unprovided for which considered, as shee hopes it willbee seriouslie by hir sone, and shuch of his frinds as are ther, wil[l] shee hopes give a Stope unto his Rueninge of his [fortune] familie, to please his fancye, sense himselfe kno[wes] that beter Maches were offerede hime befor hee went to travell, and shee belevefs not without Some resone may still bee had, more Sutabell in respect of the advantages of thar allianse, then what th[is] stranger cane bringe, soe as upon the whole Matt[er] I find shee dous not for thes resons aprove of t[he] proposistione, which and I thought it befitted mee to tell you, and if I have relatede in this, what may bee ethar displeasinge unto your selfe, or the yong gentellman; I bege your pardon for it, the which I am incoridged to hope you will grant, when to a person that has actede noe furthar then what your owne comands has warented mee to; in fathfullye returninge an accompt of what I was desired, as to the best of my understandinge I have now don, and shall with the same in integritye acquitt my selfe, on all ocations else, of your consernes as may answer, the profestione of my beinge

sir

your fathfull humbell sarvant

the 26 of No JH

This letter shows the changing power dynamic between the marchioness and her husband as she made a new life for herself and her youngest children in Dunmore and he continued his precarious existence in Continental exile.

Despite the conditions of her settlement, as this letter shows, the marchioness maintained a clandestine correspondence with her husband after she retired to Dunmore. She disguised her handwriting; she employed a range of code names to discuss her immediate family and others in her social network; and she created an epistolary persona for herself as a male friend of her husband, using the initials ‘JH’ – the same initials her friend had used when writing to her in Caen a decade earlier. Writing to her ‘delinquent’ husband in the exiled Stuart court was a very dangerous step for Elizabeth. If her letters were intercepted she could be charged with conspiracy and even treason. She was risking not only her livelihood but her life.

This letter focuses on family matters, specifically a prospective marriage for her eldest son, Thomas, Earl of Ossory. He had fallen in love with Amelia van Nassau, the daughter of the Governor of Sluys in the Netherlands. The marquis had given his cautious approval to the match, but the agreement of the marchioness was needed to authorise the financial settlement, and she vigorously opposed the marriage.

The marchioness took advantage of the unique circumstances of the couple’s clandestine communication to assert herself. By writing as the figure ‘JH’, she was able to present her own objections to the marriage in the disinterested voice of a third person: this gave the marchioness licence to be more forthright than she might have been if she was writing in her own name.

She disparages the lineage of the young woman’s family, which was an illegitimate branch of the ruling house of Orange. She rejects a Dutch connection more broadly, comparing it unfavourably with other matches closer to home. She also complains about the financial implications of the marriage: she was struggling to maintain her family on a much-reduced estate, so she reminds her husband of the mortgage on the estate, the expense of recovering it, and the dowries needed for her two daughters. She is forthright in her rejection of the proposed marriage, allowing no room for debate, and simply listing her objections without qualification or apology. Her role in safeguarding the Irish estates seems to confer on her an authority above that of her absentee husband.