16 November [1663]

The duchess of Ormonde – writing from Dublin or Kilkenny – to the queen, Catherine of Braganza

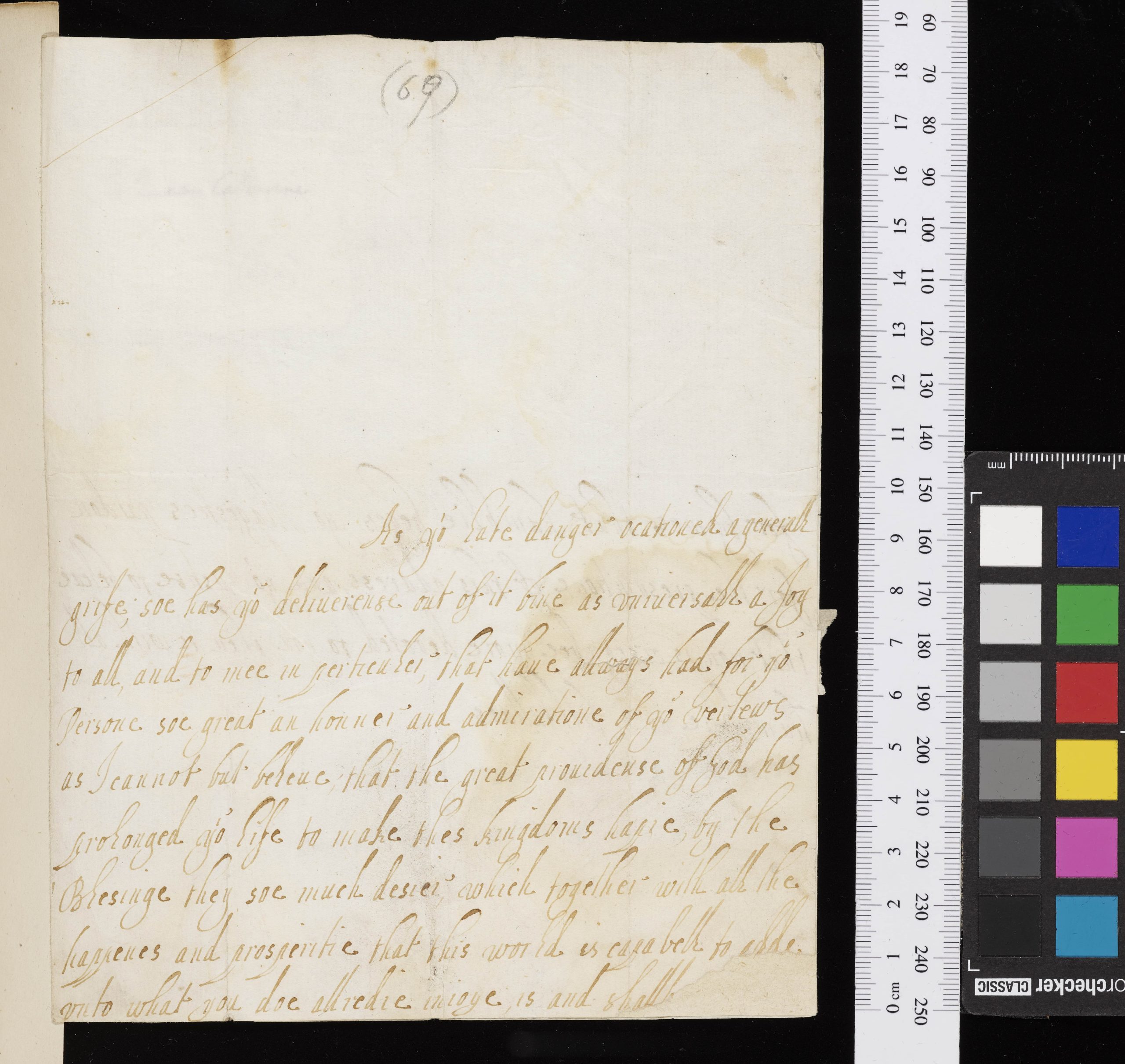

As your Late danger ocationed a generall grife; soe has your deliverense out of it bine as universall a Joy to all, and to mee in perticuler, that have allways had for your Persone soe great an honner and admiration of your vertews as I cannot but beleve that the great providense of God has prolonged your Life to make thes kingdoms hapie, by the Blesinge they soe much desier, which together with all the happenes and prosperitie that this world is capabell to adde unto what you doe allredie injoye, is and shall[bee wisht] for by mee, that humblie beges your Magesties pardon for the presumtione of this address, and your Justise to beleve that non is, or canbee more devoted to you, then is with all humilitie and fathfullnes

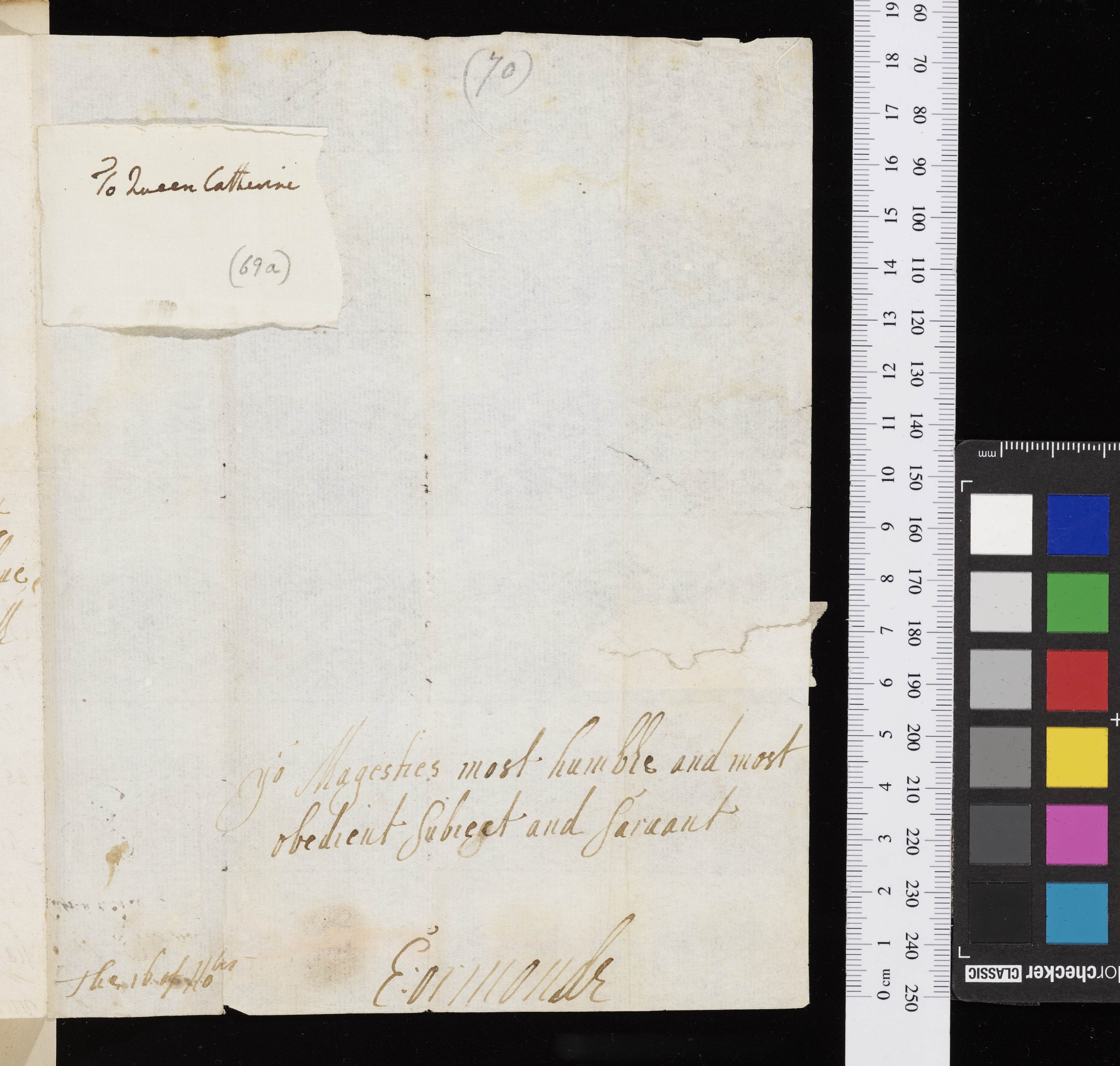

Madam

your Magesties most humble and most

obedient Subject and Sarvant

The 16 of November E:ormonde

This letter demonstrates the duchess’s intimacy with the queen, her understanding of the pressure on royal and aristocratic women to produce a male heir, and the devastation when they are unable to do so.

As Elizabeth had rightly anticipated, her family experienced a significant improvement in fortune after Charles II’s restoration as king. In 1661 her husband was rewarded for his loyalty to the crown by being made the only Irish duke. An engraving from the 1660s by the print-seller Peter Stent, featuring the duke and duchess of Ormonde alongside King Charles and Queen Catherine, the duke and duchess of York, the duke and duchess of Monmouth, the duke and duchess of Albemarle, and the archbishops of Canterbury and York, vividly illustrates the couple’s central position in the royal court.

The new duke was appointed viceroy, the highest office in Ireland, in 1662. He and his wife made their triumphal return to the country on Sunday, 27 July, accompanied by what the diarist John Evelyn described as an ‘extraordinary retinue’. They oversaw the significant development of the viceregal court as well as the flourishing of Dublin’s literary culture at this time. The celebrated poet Katherine Philips came to Ireland where her translation of Pierre Corneille’s tragedy La mort de Pompée was written and then performed in Smock Alley in Dublin.

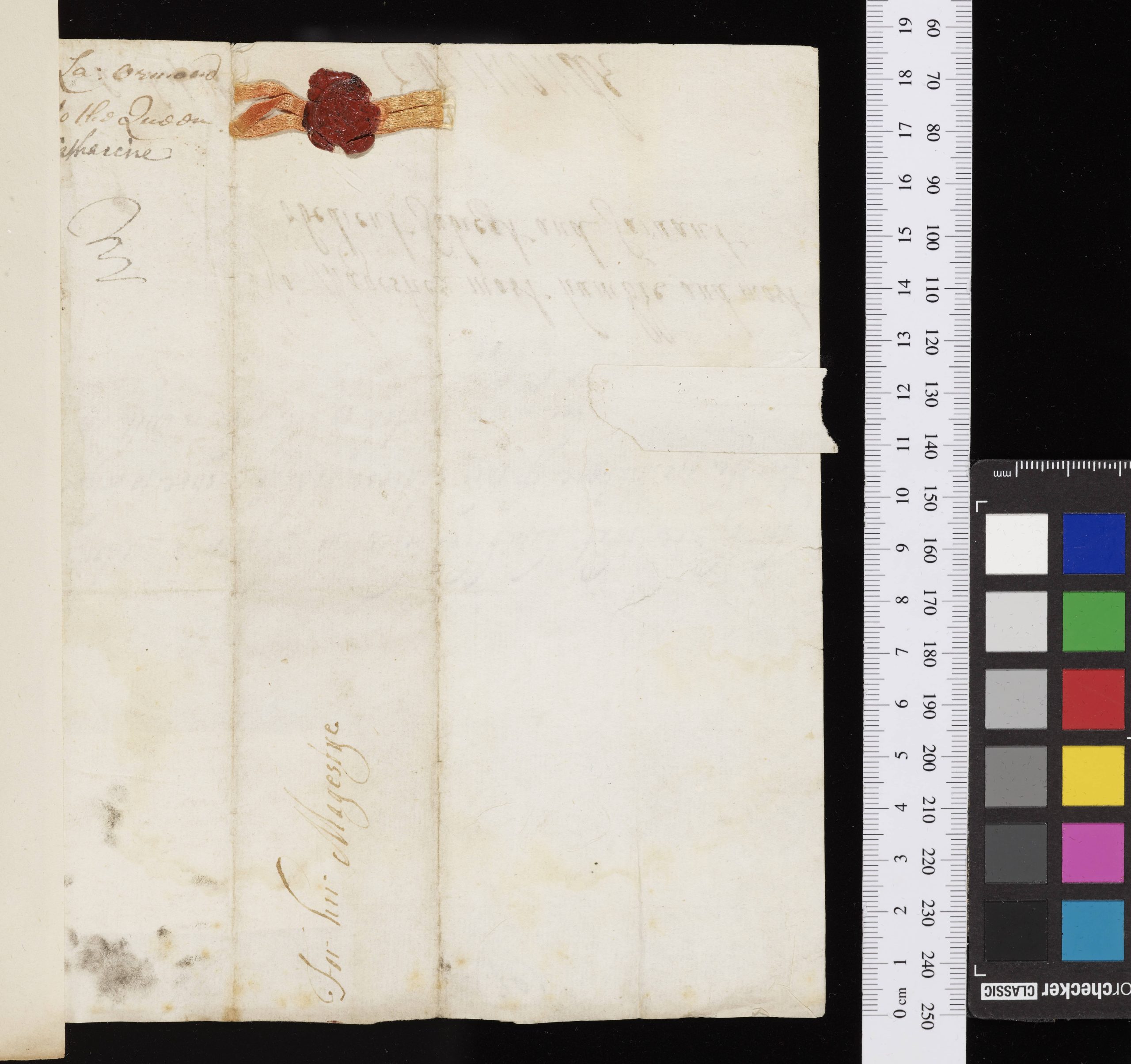

The duchess’s letter to Charles II’s consort, Catherine of Braganza, was probably written from Dublin or Kilkenny in 1663 on the occasion of the queen’s miscarriage. Her knowledge of the queen’s loss shows that she was in the inner echelons of the restored court. The letter itself is governed by the spatial conventions of the early modern letter. The writing is crouched at the very bottom of the page with large areas of blank space above the text. This rank-conscious use of what has been called ‘significant space’ signifies the duchess’s deference to her queen. The use of silk to seal the letter added a personal or emotive touch.

The content of the letter reveals the central importance of child-bearing in the lives of royal and aristocratic women. Their primary role was to produce a son and heir. The duchess’s own fertility was celebrated in poetry. During his residence at Dublin’s Werburgh Street Theatre, the playwright James Shirley dedicated a poem to her. It celebrates her fruitful marriage, which had at the time produced two sons, with a third, the future earl of Arran, on the way:

Be rich in your two darlings of the Spring,

Which as it waits, perfumes their blossoming,

The growing pledges of your love, and blood;

And may that unborn blessing timely bud,

The chast, and noble Treasure of your womb,

Your owne, and th’Ages expectation come!

The duchess’s letter to the ill and grieving queen shows her commiserating with another woman on the painful but all too common loss she had endured. Elizabeth herself had lost five sons in infancy or early childhood.